Is this what a decent life looks like?

It’s Sunday morning and your family is getting ready to go to church. Mother asks you to switch off all the lights before you leave. Electricity is expensive she says. You hear the toilet flush so you know that your sister is finally finished in the bathroom. Your grandfather is watching television. He is not going with the family. He says he is tired of church. He says he has a better chance of finding God on Kumbul eKhaya.

The church is close by, so you don’t have to take father’s car. It needed repairs recently, but fortunately the family had some savings to have it fixed. The car helps in a lot of different ways, although father complains that it is very expensive. He says it is like having another child.

It’s a chilly morning and everyone is wearing their coats, although it’s warm inside the house. Eventually everyone leaves, except grandfather, and you close the gate behind you. You look at the house before you go. It’s a modest house, but it’s a nice house. The last one would leak when it rained. It worried you, the sound of water dripping into buckets.

A few street lights are still on. Mother tells everyone that the municipality is wasting money. Although it is cold, the air is crisp and clear. You can see for miles on mornings like this. The road is tarred and the streets are clean, so everyone’s shoes are still shiny when they get to the church.

On the way back home you run into the supermarket to buy milk so that you can make tea for everyone.

You might prefer a rural setting, you might imagine a smaller family, and you might not be Christian. Even so, I doubt you would disagree with some of the key themes embedded in this story. You would not say that having electricity in the home is only important to some. You would not argue against the importance of having running water and flush toilets in the home. You would not suggest that a decent home is culturally relative. You would support the ability of people to participate in social and cultural activities near where they live. You would agree that having basic services and amenities close to where you live was important.

Despite a long running debate on poverty and inequality in South Africa, we have not had a robust measure of what it is to live, not merely to survive, but to live decently. Simply put, we do not know what a decent life looks like.

Nor do we have a sense of the income level associated with a decent life. The incomes reflected in social dialogue and policy instruments are largely arbitrary. Why is the child support grant R400 per month? Why is the national minimum wage R3500 per month? You might say that social grants are shaped by budget constraints. You might say that the economy cannot afford a higher minimum wage. What you are really saying is that these amounts are more than nothing. What you are really saying is that you don’t know how much we need for a decent life and you don’t know what a decent life looks like.

We disguise our ignorance by talking about jobs. If everyone could just have a job, then we don’t have to worry. But we do have to worry. There is no evidence that the South African economy has the ability to meaningfully grow employment, even under conditions of modest and sustained growth, conditions that are an increasingly distant memory.

It is therefore, hardly a surprise that we do not have clear pathways to a decent standard of living. It follows that efforts to move households from poverty towards decency are difficult to conceptualise, implement, coordinate and to measure.

A new way of looking at a decent life for all

The Decent Standard of Living (DSL) measure focuses on the ability of people to achieve a socially determined acceptable standard of living to enable them to participate fully in society. The starting point for this measure was a set of indicators of a decent standard of living. There was a high level of agreement around these indicators across different sections of society including population group, gender, area type and income status. A set of ‘socially perceived necessities’ (SPNs) were defined as essential by a two thirds majority of South Africans.

The list is a set of indicators, rather than an exhaustive list of necessities. This approach provides an elegant escape from the immense difficulty of determining the quantity and quantity of a basket of goods that is both representative of the population and also finite.

Percentage of people defining an item as ‘essential’ with consensus of two thirds or more

| Item | % Defining essential | % Possessing item |

| Mains electricity in the house | 92 | 89 |

| Someone to look after you if you are very ill | 91 | 83 |

| A house that is strong enough to stand up to the weather e.g. rain, winds etc. | 90 | 70 |

| Clothing sufficient to keep you warm and dry | 89 | 79 |

| A place of worship (church/mosque/synagogue) in the local area | 87 | 93 |

| A fridge | 86 | 74 |

| Street lighting | 85 | 55 |

| Ability to pay or contribute to funerals/funeral insurance/burial society | 82 | 71 |

| Having police on the streets in the local area | 80 | 54 |

| Tarred roads close to the house | 80 | 59 |

| A flush toilet in the house | 78 | 41 |

| Someone to talk to if you are feeling upset or depressed | 76 | 84 |

| A neighbourhood without rubbish/refuse/garbage in the streets | 75 | 57 |

| A large supermarket in the local area | 75 | 53 |

| A radio | 74 | 45 |

| Someone to transport you in a vehicle if you need to travel in an emergency | 74 | 64 |

| A fence or wall around the property | 74 | 71 |

| Being able to visit friends and family in hospital or other institutions | 73 | 88 |

| Regular savings for emergencies | 71 | 32 |

| Television/TV | 69 | 84 |

| A neighbourhood without smoke or smog in the air | 69 | 57 |

Source: For % defining essential: South African Social Attitudes Survey 2006. For % possessing item: Living Conditions Survey 2014/15.

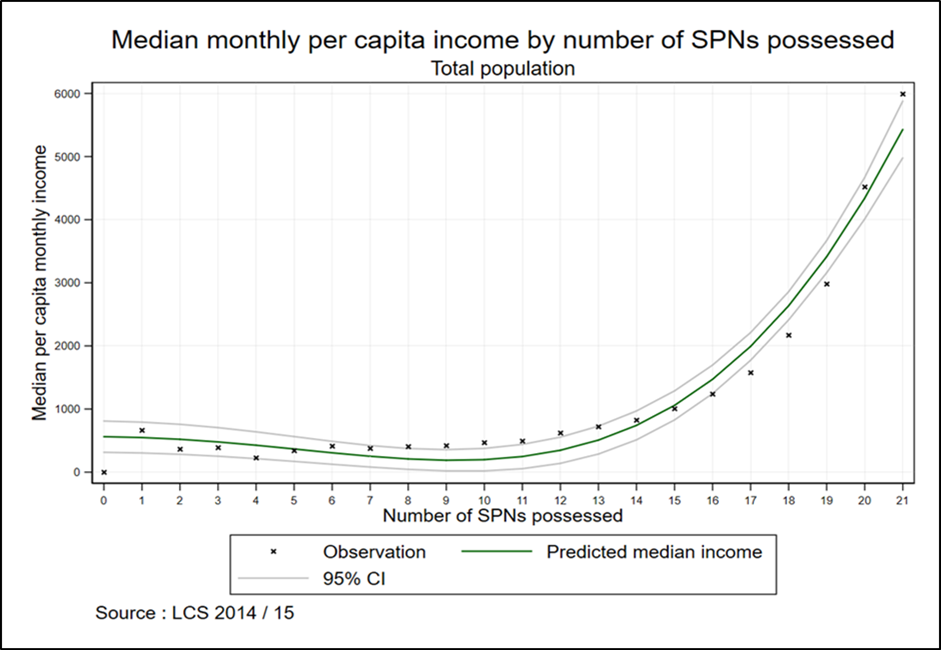

The Living Conditions Survey (2014/15) shows that there is a clear relationship between per capita median income and the number of necessities possessed,although this is not a linear relationship. The number of necessities that are possessed by households increases as median per capita income increases, rather unsurprisingly, although the mix of SPNs at each level might differ.

Median monthly per capita income by number of socially perceived necessities possessed, 2014/15

We constructed a Decent Standard of Living Index (DSLI) so that the income level associated with a decent standard of living (DSL) can be continually adjusted to keep it up to date in current prices.

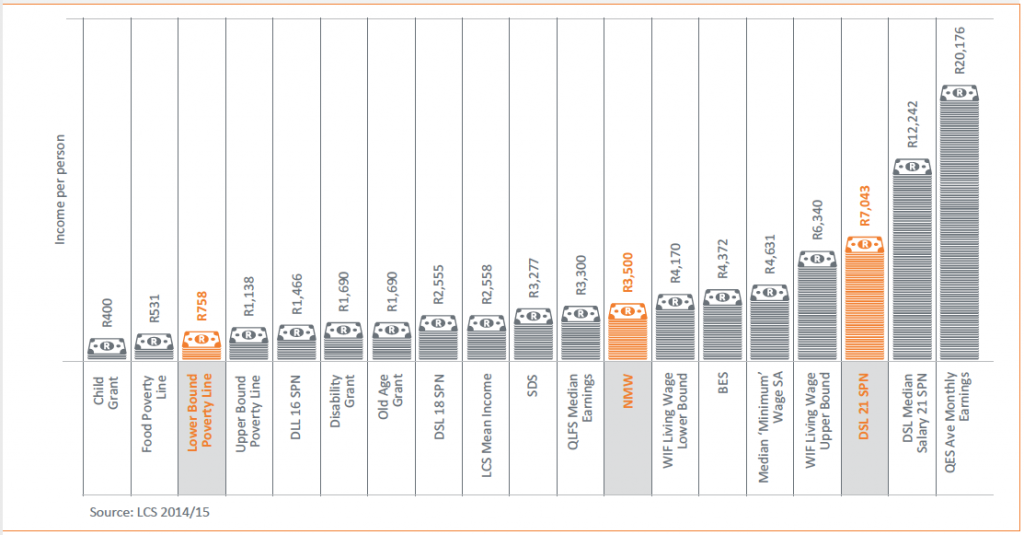

The median per capita income associated with a decent standard of living in April 2018 was R7,043 per month.

The national minimum wage sits at about half (50%) of the per capita income associated with a decent standard of living – a life without struggle. There is a vast distance between social grants and the median per capita income associated with a decent standard of living (DSL). The Child Support Grant is 6% of the decent standard of living amount, while the Old Age Grant is about a quarter (24%) of the decent standard of living.

Benchmarks of income, earnings and a decent standard of living in South Africa, 2018

We explored the relationship between the possession of necessities and earned income by looking at the median monthly salary of each adult earner within each household containing an adult earner for each number of necessities possessed. In simple language, what is the wage level associated with a decent life? The median salary associated with households possessing all 21 SPNs was R12,028 at April 2015 prices. The national minimum wage of R3500 per month is associated with the possession of about 15 out of 21 SPNs.

What does it all mean?

At risk of disappointing those of you impatient for significant change, we are not saying that a decent life costs this or that amount. What we are saying is that a decent life is associated with certain measures of income. There is an important difference between the two statements. As much as we would love to see median per capita income of R7000 per month in all South African households, we are not saying that this is what a decent life costs. As much as we would like to see median wages in excess of R14000 per month for all wage earners, we are not saying that this salary level is required for a decent standard life.

The highly unequal distribution of wealth in South Africa is likely to shape the incomes associated with the possession of socially perceived necessities. Put another way, it is perhaps likely that South African households that possess all the socially perceived necessities have higher per capita income than is required to possess all of those necessities. Conversely, household per capita income associated with households possessing relatively few socially perceived necessities might not reflect the strain of acquiring those necessities or the ingenuity and social networking strategies deployed to acquire those necessities.

It is also not our intention to monetise or commodify all aspects of a decent life. The decent standard of living measure offers us an opportunity to examine what the different aspects of a decent life might be. The decent standard of living measure is an opportunity to see new pathways to a decent life and this is perhaps the most important aspect of the approach.

This approach makes it possible to consider how households can acquire each of the socially perceived necessities. We identify three broad categories or modalities of acquisition. Households can acquire social perceived necessities through (1) social networks, (2) the social wage and (3) the purchase of commodities.

The first category is that of social networks. As an example, socially perceived necessities such as ‘someone to talk to when you are upset’ can be acquired through the household’s own social networks rather than bought.

A second category is that of the social wage, understood here as goods and services that are best provisioned by the state. Socially perceived necessities that could be considered as part of a social wage include ‘tarred roads close to the house’ and ‘street lighting’.

A third category is that of commodity, simply put – goods or services that can be bought with money. Examples of socially perceived necessities likely to be acquired in this way include a refrigerator and funeral insurance.

These broad categories of acquisition are not mutually exclusive. For example, a household may commodify the acquisition of tarred roads close to the home and street lighting by moving to an area where this infrastructure is better developed. This is a however, a relatively expensive mode of acquiring a necessity and there will be significant barriers to entry for many households.

It is no coincidence that socially perceived necessities that can be acquired through social networks are likely to be possessed earlier rather than later. If we consider the socially perceived necessities from the point where the curve of associated incomes becomes steeper (the ‘late jumpers’), we find that a number of them may be classified as elements of a social wage, including street lighting, police on the streets in the local area and a neighbourhood without rubbish in the streets.

The implication is that the development of quality, targeted community infrastructure is likely to assist households in acquiring many of the ‘last mile’ necessities.

The DSL offers more than a series of thresholds around which we can measure how many are below and how many are above. The DSL offers us ideas about how to move households towards a socially-derived vision of a decent standard of living. This decent standard of living measure provides a framework and rich source of data for future analysis and for informing policies regarding both public and private provision and acquisition of necessities in order to guide and facilitate the realisation of a democratically derived decent standard of living for all in South Africa.

Trenton Elsely is the Executive Director of the Labour Research Service.

The decent standard of living project is a collaboration between the Labour Research Service, The Studies in Inequality and Poverty Institute and the Labour Research Service and Southern African Social Policy Research Institute.

Recent Comments