By Dr Gemma Wright & Jabulani Jele

We now have a socially derived definition of a decent standard of living in South Africa.

Dignity is a vitally important value in South Africa, both culturally and in the jurisprudence literature. The constitution places dignity at centre stage, stating that “everyone has inherent dignity and the right to have their dignity respected and protected”.

Research that we have undertaken over the past years has exposed ways in which not only poverty but also inequality, erodes people’s sense of dignity. It has also helped highlight that a sure-fire way in which to respect and protect dignity is to eliminate poverty and reduce inequality.

Focus groups that our colleagues have undertaken have found detailed accounts of the detrimental impact of poverty on dignity (including being treated as a burden, strained family relations, and being unable to afford to escape abusive relationships which we have seen recently in the media).

They have also demonstrated that attempts to escape poverty are often experienced as undermining of dignity too (eg, having to do demeaning work for friends and family, transactional sex, tolerating intolerable jobs). It shouldn’t be this way.

The nationally representative South African Social Attitudes Survey (SASAS) has helped us to gauge social attitudes about these issues. Questions that we included in this survey in 2012 revealed that more than 80% of respondents agreed or strongly agreed with the statement that “poverty erodes dignity”, and three-quarters of respondents agreed or strongly agreed with the statement “the gap between rich and poor people in South Africa undermines the dignity of us all”.

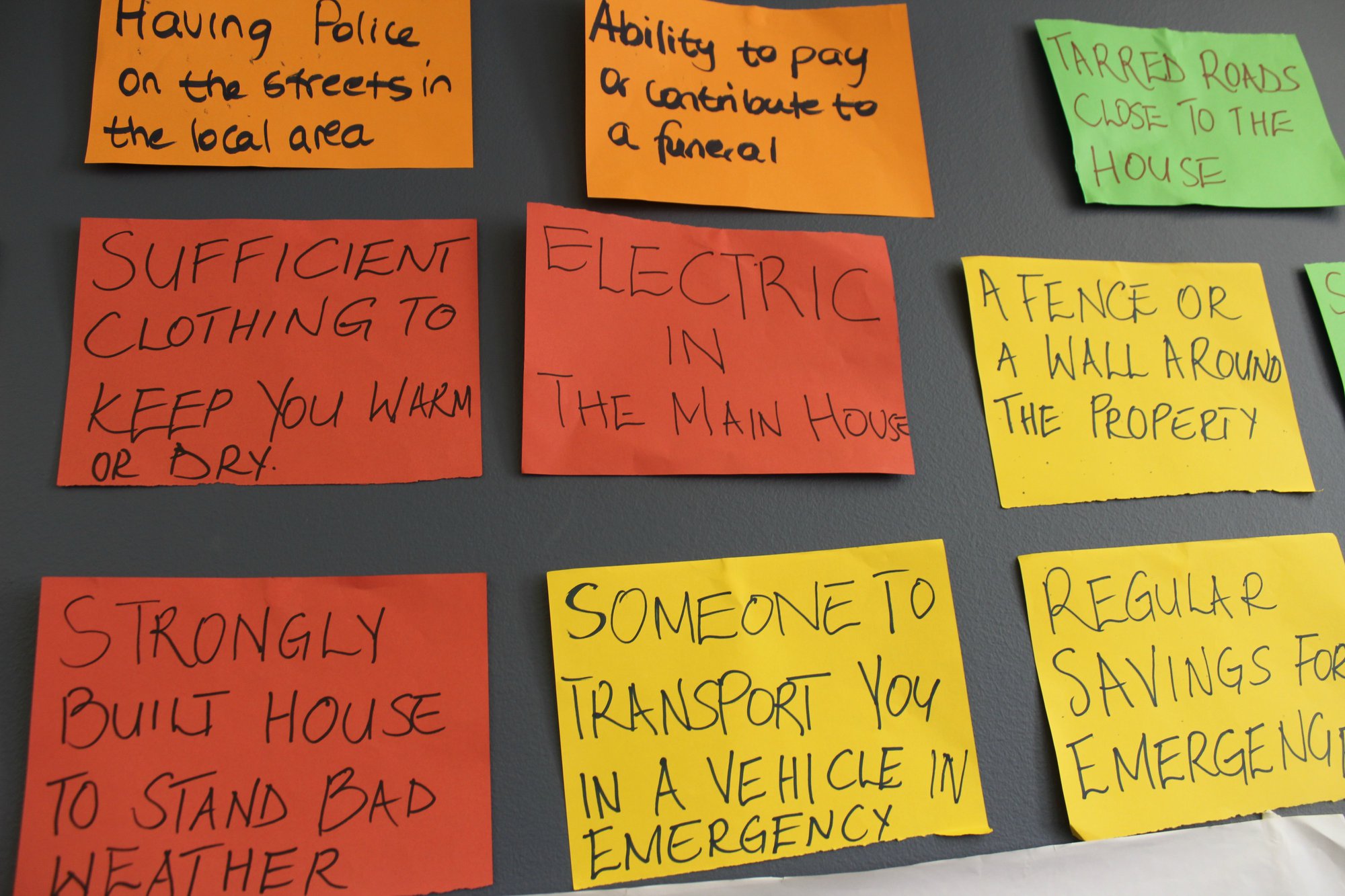

We now have a socially derived definition of a decent standard of living in South Africa. This provides us with a solid benchmark to assess how far we are away from a situation where dignity is properly respected and protected. The bad news is that this socially-derived decent standard of living is only enjoyed by a tiny fraction of the South African population.

For example, one of the items included in the definition of a decent standard of living is to have a flush toilet in the house. The most recent Living Conditions Survey reveals stark spatial inequalities: although almost 95% of people in urban formal areas have a flush toilet, less than half of people have a flush toilet in informal settlements, and almost nobody does in traditional areas (just 4%).

The good news is that there is huge support for protecting dignity and reducing inequality: in the same SASAS 2012 module, 94% of respondents agreed or strongly agreed with the statement “it is important that the government respects and protects people’s dignity”.

In 2017, a question in SASAS asked people to respond to the statement, “the government should provide a decent standard of living for all unemployed people”. Although we know that there is sometimes an ambivalence towards unemployed people, a huge 84% of respondents agreed or strongly agreed with this statement.

Importantly, there was broad agreement between poor and rich people.

For example, of those who reported in the same survey that they found it “very difficult to make ends meet”, 88% agreed or strongly agreed that government should provide a decent standard of living for all unemployed people, and of those who said that it was “very easy to make ends meet”, 73% agreed or strongly agreed.

As the retired constitutional judge Laurie Ackermann has argued, human dignity is the lodestar for equality in South Africa. The socially derived definition of a decent standard of living provides us with a map to help us get there. There is an appetite for structural interventions to achieve a decent standard of living, and they need to happen better and faster as there is simply no time to waste.

Dr Gemma Wright is research director at the Southern African Social Policy Research Institute (SASPRI).

Jabulani Jele is a Research Officer at SASPRI

The decent standard of living research project is a collaboration between SASPRI, The Studies in Inequality and Poverty Institute(SPII) and the Labour Research Service.

This article was first published in The Citizen.

It all depends on the choices people make in the polling booth. If people choose organizations that do not have their welfare at heart, sympathy is wasted on them. SA people have made their bed, now is bedtime

Where would all this money come from to provide the decent standard of living? We all seem to be living in cloud cuckoo land when it comes to these social issues. The tax base to fund these initiatives is shrinking. This environment of entitlement has to stop.

If you keep electing a corrupt and inept government that steals and plunders the coffers then you must expect to farm backwards. Elect a government that stops corrupt practices, focuses on job creation, gets rid of corrupt officials without massive handouts, abolish practices like BBBEE as this only serves to benefit the corrupt politicians who gleefully line their own pockets.

It has been 25 years since the democratic elections and the generation of qualified young black graduates should be starting to filter through to the economy. If I were black I would probably feel more than a bit annoyed that I was getting a job based on my colour rather than my ability. Furthermore, the education standards have dropped I believe due to government intervention. In order to show progress in the education sector the pass mark has been dropped substantially to be able to show higher pass rate. This seriously dilutes the credibility of those young black graduates who have passed their degrees.

South Africa is a country rich in resources. However, the value in these resources does not lie in the mining of such but in the beneficiation of those resources. Don’t export the raw goods, add value then export the finished or semi finished products. Have more technical training facilities to teach young people alternative skills. We already have way to many political science graduates. Get people to study skills that actually help and grow the economy. Teach innovation and entrepreneurship in schools.

Allow people to start their own businesses with interest free or low interest loans rather than humiliating state handouts